“Who Own Science” was the title of a free public lecture given by Sir John Sulston in Cambridge on Wednesday 5th November. Sulston was giving the Cambridge Philosophical Society’s Honorary Fellows Prize Lecture for 2008. The title had been borrowed from the opening of “The University of Manchester’s Institute for Science, Ethics and Innovation” at which Sulston had also spoken.

I attended this lecture partly because I think the question of “Who owns Science?” is an important one. A lot of public money, and latterly charitably raised funds get channelled into scientific research but all too often the fruits of that work are not accessible to those who are paying for it. Too often decisions on what areas are worked on are not being made by those supplying the funds. I think that in the UK we ought make the publications, and some other outputs arising from our publicly funded research available to all. We should not be afraid, as a nation, of directing our scientists and telling them what we want them to work on.

As well as addressing the subject of his lecture, Sulston had been asked to give a biographical presentation. He was able to combine the two explaining how he had spent a “whole career on producing raw data” and accepting his opinions were coloured by the type of data he had been working with. During his early professional days working on the developmental pathways of the model organism Caenorhabditis elegans he said he had benefited from the open sharing of information between researchers, largely facilitated by their physical proximity within the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology at Cambridge.

Slides describing his early work included one showing the cell linage of c.elegans and micrographs showing cell death occurring at constant points in the development of the organism, with dying cells appearing as bright spots due to becoming more refractive as proteins within them were being released.

Sulston put forward an the idea of there being “fundamental datasets” which ought to be public, he accepted that it was not easy to define what ought to come into this category. Data produced during the Human genome project was given as a clear example. Sulston is credited as being a key player in obtaining accord known as the the Bermuda Agreement, ensuring the public consortium’s raw sequence data was published daily. I agree this is an excellent model which has now been followed not only by subsequent sequencing projects, but by particle physicists and astronomers.

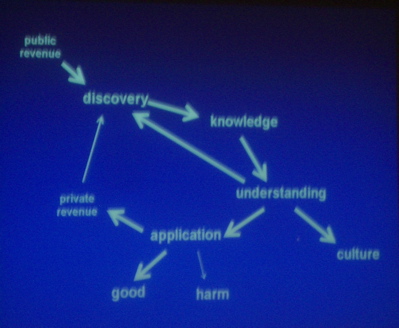

The lecture went on to consider how science is funded. Quite shockingly in my view Sulston stated that in his opinion public money being put into science is defined as not looking for any financial gain. He claimed that the Regan/Thatcher era had strengthened private revenue streams funding scientific work, but at the expense of public funding. The Thatcherite view was summarised: “We can make all this money out of science, so why do we have to put public funds in?”. Sulston said that he felt that the existence of “uncontrolled experts” was very important, and claimed that there were no longer enough truly independent experts in science due to private, commercial funding. Commercial contracts requiring universities not to publish results which their funders would consider adverse are still being written claimed Sulston.

As an example of the importance of an independent science base Sultson used GSK’s Relenza influenza drug. Sulston claimed Relenza was only put onto the list of drugs which can be routinely used in the UK’s NHS by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence following a threat from GSK to leave the country.

Sulston introduced the commonly quoted figure of the total number of new drugs licensed by the FDA between 1975 and 2004 as 1556. He noted there was not enough emphasis on tropical diseases and a focus on the diesases of the rich countries. We were, and are, he said piling into a small number of targets for example cholesterol or serotonin receptors, and put up a slide stating 75% of new drugs have no additional therapeutic benefit.

The role of democratic Government was described as being to balance:

- Industry (Driven by profit)

- Science (Driven by discovery)

- Medicine (Driven by helping patients)

Partly in jest, partly to get a response and partly seriously Sulston said:

A recent publication by T Hubbard and J Lowe in which they argued that there was a need for public stimulated R&D which would influence commercial R&D was introduced. The argument made was that currently the public have little influence over where commercial organisations spend their research money. Sulston noted that many of the companies which conduct significant amounts of research are public companies, owned by all of us who have savings or pensions. The use of prize funds to direct research was also mentioned; though I am not clear if Sulston was proposing public money should be put up as prizes, I think he was.

Universities Allied for Essential Medicines (UAEM ), a student pressure group which puts pressure on universities to license their intellectual property on “globally equitable terms” was mentioned. Later in response to audience questions Sulston expanded on what he saw as the importance of students taking a role in shaping universities’ policies. He said “Students have to put pressure on Universities, they’ve got no mortgages and they don’t need to keep their jobs. Students need to have a role in directing Universities.” Universities ought to play a leading role in a wide range of societal issues, for example tackling problems with the intellectual property system and commenting on trade rules.

Sulston briefly considered the good / harm which can be done by science and the application of its results. He said: “without exploration there is no point”, and

“We might be alone in the universe, the survival of humanity is important – we have to hang on to that”. I share those sentiments.

There was no specific discussion of open access publishing during the lecture; I believe various charities and the Welcome trust are now have stronger polities in this area than universities themselves or the research councils, I was surprised by this omission.

I felt it was quite ironic that Sulston chose the Cambridge Philosophical Society to give this talk too, given that they are themselves an elitist group, though they do hold public events such as this one. From their website: “any person desirous of becoming a Fellow must be recommended in writing by a Fellow of the society who has been a member for at least three years and a person of appropriate standing, who knows the candidate personally in a professional content”. The organisation is divisive within Cambridge with respect to graduate students because its members are eligible to apply for grants from the organisation, which are seen by many as an integral part of the University’s support. I believe that if the University is going to support the society, as it does, there ought be a more accessible meritocratic route to membership.